To discuss social anxiety, we're going to start talking a little bit about evolution.

In evolution, we, well, evolve things.

For example, we have organs like the appendix that used to be useful to us as humans, but they're not necessary anymore. These are called vestigial organs or limbs.

A lot of times, evolution will leave behind vestigial parts that no longer serve a function.

What's happening right now in society is that going outside used to be a basic need, and now it's not that necessary anymore.

Going outside, to a certain degree, has started to become vestigial.

We have grocery and food delivery; we can hang out on Discord, Twitch, FaceTime, or social media; we can work online, and have a whole community online!

When life is changing, and what we need to survive is changing, there's a lot of judgment that comes along with it.

For example, when articles criticize younger generations for not knowing things that used to be expected, like changing a tire, building things, etc.

The difficulty of going outside can come with a side of shame, making it harder to face this.

The thing is, you actually don't need to go outside, but it's still healthy if you do. You're probably going to suffer if you don't go outside. But start by doing away with the shame and self-blame.

We can also think of this difficulty from a societal point of view. What kind of society exists that allows people to grow without really learning how to "go outside"?

What kinds of circumstances must exist for some to evolve in this state that we're in right now?

What has to happen in our society that going outside becomes vestigial and a thing of the past?

Nobody is fundamentally messed up if they don't know how to go outside. This is a societal occurrence and shouldn't be treated with shame.

It's important to differentiate this from agoraphobia. The latter is a disorder, and what we're discussing is actually generational and societal, but not necessarily pathological.

If you're having trouble going outside, don't over-complicate it with different goals at the same time. For example, don't go out looking to make hobbies and make friends at the same time.

The first thing you should do is literally go outside. Grab a book, a kindle, a phone, and go outside for a walk, library, park, or any other public space that's socially acceptable for you to be alone.

Go to a public space and simply hang out by yourself.

At the start, don't even worry about interaction, just go outside and do simple activities by yourself.

You might feel the urge to avoid these situations, but start by occupying yourself.

You want something to do because if you feel socially awkward, you need to have something at the beginning to alleviate that social awkwardness and do something socially acceptable.

Start by just going outside, sitting at a park bench, taking a walk, doing some reading, and then coming home.

The important thing is that you're leaving the house and doing activities outside, even if you're by yourself.

Some activities might be listening to an audiobook or podcast while on a walk; reading a book on a park bench; going to a museum or exposition; going to a farmer's market.

Do that ideally for 2 to 3 times a week, and when you're ready, bump it up a notch.

Go to a bookstore and ask for help, actually interact with other people, just for the sake of the interaction. You don't need to do it with the objective of making friends.

The next step is joining maybe a club or group activity.

For example, if you go to a bookstore, ask if there's a book club that you could join. Or if you like walking, look for planned group hikes.

For people who are concerned about social interaction, the main thing is focusing on the activity or hobby first, and the social interaction second.

Recognize that people aren't in these places to necessarily make friends, and if you don't make friends, that's not a big deal.

Always focus on the activity at hand, and after a few tries, you're bound to get friendly with people.

Friendship is going to be an organic happening. Once you hang out with people on a regular basis, it will start to happen.

Making friends usually requires a couple of things:

1. Repeated unplanned interactions

You have to, basically, run across the same people over and over again. That's why it's easier to make friends at school, for example.

2. Common cause

You have to have a shared goal that you unite around. For example, in a class, you can have a common goal of passing a test, then you start exchanging notes and studying together.

It is hard overcoming social anxiety, but focusing on these steps can make things easier.

And remember, like any other activity, things will become much more natural with a lot of practice!

Anxious-Avoidant Attachment happens when, as a child, the person communicates their emotional needs to their caregivers, and they either got no response or neutral response.

For example, a child might have a nightmare and call out for their caregiver during the night. In turn, the caregiver doesn't comfort the child and instead ignores their cries of distress. They might even get irritated by their kid's show of emotions.

These situations can cause a belief that voicing your needs doesn't get a response. So the child ends up becoming very independent, but it's just a mask for their emotional distress, protecting them from getting hurt again.

A person with an anxious-avoidant attachment style keeps partners at arm's length because of their fierce independence and coldness in a relationship. They might always have an exit strategy in a relationship because they avoid commitment and intimacy, leaving their partner feeling unreassured.

It's also rare for them to willfully talk about their feelings with their partners, and they tend to shut their significant others out.

Because of their apprehension of being intimate with significant others, the anxious-avoidant person can produce a lot of insecurities in their partner. In turn, the partner keeps wondering if they are loved back.

These insecurities can lead the partner to accuse the anxious-avoidant person of neglect, selfishness, betrayal, or egocentricity. When this happens, the avoidant person can become more distant and even lash out, blaming the relationship's problems on their partner.

To make a relationship with an anxious-avoidant person work, it's important to remember that their distant attitude comes from fear of letting down their guard and being betrayed or abandoned.

They put up barriers not because they don't care but because being intimate and exposed is very unfamiliar for them.

Getting into blame games will only make the avoidant person retract further, so the best solution is directly addressing each other's fears.

For them, vulnerability is frightening and thought to get them hurt, so their partner can do their best to make closeness feel safe. This includes viewing their tendency to isolate from an empathetic point of view rather than a punitive one.

Lastly, the partner of an anxious-avoidant person should also examine their feelings towards closeness or intimacy. It can happen that they could've picked out someone closed off precisely because they are afraid of closeness.

Because the anxious-avoidant person is always distant and highly independent, it's easier to pass the share of the problem to them than face your own fear of intimacy.

Whatever the case, this kind of relationship requires a lot of empathy and understanding regarding different coping techniques so that both partners can acknowledge and accept the risks of a loving relationship.

References:

Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment style happens when caregivers give inconsistent responses and caregiving to a child. The caregiver is loving and attentive at times and unavailable and aloof at others.

For example, the child might

This pattern of behavior can cause the child to be confused and question whether they'll have their needs met. In addition, they have a hard time understanding what their caregiver's actions mean, resulting in extreme inner turmoil.

A relationship with an anxious-ambivalent person is characterized by mixed signals.

The person with this attachment style can get angry, frustrated, or upset with their partner. Still, they don't validate their feelings, so they end up feeling stupid because of them.

This self-judgment leads to the person not communicating their problems to their partner, causing issues and miscommunications in a relationship.

Moreover, these people feel insecure about their worth in a relationship, so they constantly need reassurance that they're loved and valued.

This intense insecurity can lead to clinginess and, at times, extreme jealousy and suspicion in their partner.

So, at the same anxious-ambivalent people deeply crave feelings of closeness and intimacy with their partner, they also struggle to feel like they can genuinely trust them.

Because of their constant worries and insecurities in a relationship, anxious-ambivalent people need to have constant reassurance from their partners that they're loved and valued.

This reassurance can be done in many different ways, but it must be consistent and truthful.

Validating your partner's feelings is also an essential step in leading them to a more secure attachment. Validating doesn't mean agreeing with everything they say. Instead, delicately point out evidence of you and your relationship's stability when your partner starts questioning it.

References:

The article fits more for the kind of people that meet the following criteria: people confused by inner turmoil, that feel that other people do a lousy job at relationships but have a hard time articulating what they're doing wrong, someone that feels cold or numb in a relationship, keeping others at arm's length. It happens most commonly for men due to the way they get raised and conditioned.

From a partner's perspective, this looks like receiving mixed signals, such as your partner getting in a mood but saying nothing is wrong. Other times, the partner gets mad over small things. Lastly, the partner keeps you at arm's length. Again, this pattern is most common with men.

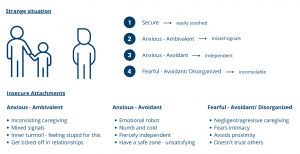

The Attachment Theory was created by John Bowlby, where he studied a "strange situation.” In this situation, a kid is with their mom, who leaves, and then a stranger walks into the room. After a while, the mom enters the room again. There were different ways in which a kid responded to this situation.

The Four Types of Attachment

1. Secure attachment

The kid may cry or be in distress when the stranger enters the room, but they’re easily soothed when the mom comes back.

2. Anxious-Ambivalent

The kid cries, but when the mom comes back, they get frustrated, angry, and confused.

3. Anxious-Avoidant

The kid cries as well, but they don't go to the mom for comfort when she comes back. They become independent.

4. Fearful-Avoidant/ Disorganized

They freak out when mom leaves the room, and they become inconsolable, even when she gets back.

The anxious-ambivalent attachment style develops when caregivers give inconsistent responses and care giving to the child. Sometimes the caregiver is warm and loving, and other times they can be cold, distant or neutral. That way, the child never knows what to expect.

Children learn to feel their emotions by mirroring other adults; they know what they're feeling through the emotional expressions of people around them. So it gets confusing when they receive inconsistent responses from their caregivers.

The type of care these people received during their childhood results in a clinical presentation of mixed signals, either external or internal. One example is that a person can be mad and send signals that they’re angry, but they say they’re fine when asked how they feel.

Consequently, the people with this attachment style feel inner turmoil. They get angry or frustrated and feel stupid because of it. They can be ticked off in a relationship, but they cannot articulate why they’re bothered.

Another trait that can be found in people with this attachment style is low self-esteem.

Relationships can be challenging for anxious-ambivalent people because when something upsets them, they can't communicate to their partner what they did wrong. What happens is a sense of self-judgment, where they feel like they shouldn't feel this way. The person ends up not sharing their feelings, and it creates problems in the relationship.

The anxious-ambivalent attachment style is called a resistant attachment, characterized by feelings of anger and helplessness. The people who have it seek contact and also rebuff it, so there’s a part that wants more in a relationship and another part that doesn't want to get hurt again. It's a protective mechanism that the person engages in.

This can also lead to an intrinsic lack of motivation because the person is on the fence about things they want, afraid of not getting it.

The anxious-avoidant attachment style is caused when a child communicates their emotional needs, but they get no response or a neutral response from their caregivers. Basically, they learn that voicing their needs does not get a good response.

The people that present this attachment style can often feel like "emotional robots". These people are seemingly numb, cold, and fiercely independent.

The way they were cared for as kids creates a problematic cycle where even if the person communicates their needs, they're not good at it, so they feel rejected. The more rejected they feel, the more independent they become, and they end up withdrawing. They withdraw but don't leave, staying at the threshold of a relationship.

In a relationship, anxious-avoidant people have a safe zone where they stay independent. However, the safe zone is unsatisfying because they realize they're missing something in the relationship but don't know what to do about it. Because of this situation, they keep their partner at arm's length.

It can even happen that the person is afraid of being dependent on their partner.

They may appear calm, but it's a mask for their internal distress, protecting them against emotional hurt.

This attachment style mostly happens to men because of the way they were raised, with commonly repeated phrases like “boys don’t cry” or “man up”.

The disorganized attachment style carries different names, depending on the author. However, it’s believed to be the most difficult kind because of its origins and characteristics, as it can be a result of childhood trauma and abuse.[1] [2]

This attachment style develops when a caregiver constantly fails to respond accordingly to their child’s distress, often in a negligent or aggressive way. When that happens, what was supposed to be a source of safety for the child becomes a source of fear and unreliability; they don’t know what to expect from their caregivers, and don’t know if their needs will be met.

As an adult, the person with disorganized attachment fears intimacy and avoids proximity. They’re waiting to be rejected and hurt by their partners, and view their attachment figure as unpredictable.

The person with this attachment style also exhibits characteristics of anxious - avoidant and ambivalent styles and can feel like they’re ineffective or helpless in life. They are at a higher risk of developing mental health issues such as substance abuse or aggressive behavior.

The characteristics of a disorganized attachment style can lead to self-sabotage or to a self-fulfilling prophecy, either when the person starts seeing signs of rejection that aren’t there, or when they choose a partner that induces fear, confirming their belief that they can’t trust others.

In a relationship, these people worry that their partner doesn't love or support them, and they can alternate between clinginess and detachment.

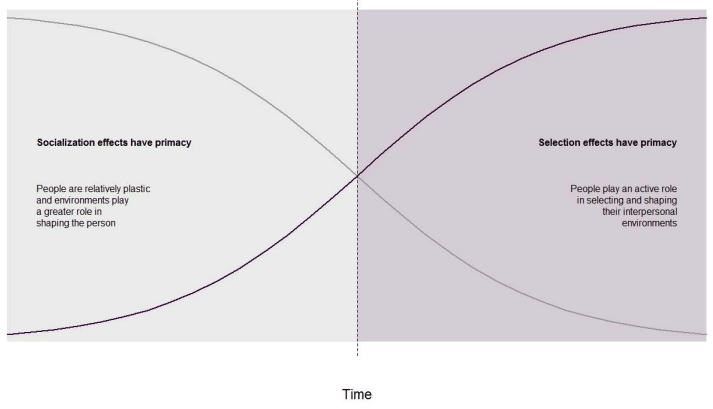

What Bowlby hypothesized is that all this happens in childhood. That's not true, because 'foundations are not fate.’

When you're 1 year old, the attachment style is totally determined by your caregivers. As you grow up, this matters less and less, and what really starts to matter is the selection effect. People play an active role in selecting and shaping their interpersonal environment; however, they still might choose based on what they learned from their parents.

If you have any kind of insecure attachment as an adult, you should share your feelings, even if you don't understand them, and the partner can be confused with you. Fixing your attachment style is not about figuring out the answer; it’s about not facing your problem alone. It's about emotional mirroring, not emotional correction. It's about the other person meeting you where you're at. That's why you should be careful with the people you hang out with; try to find people you can share a half-baked thought with.

Another step is to acknowledge your own emotional needs, even if you don't understand them. Acknowledge whatever you can. Understand that your partner doesn't need to fulfill your emotional need, but it's essential to accept and communicate it.

Fixing your attachment style has to do more with awareness than changing your behavior. It’s about acknowledging your personal needs and sharing them for emotional mirroring with other people. The partner needs to hear you and mirror it back.